|

The crisis in our music community is real. By proposing the creation and internet law, the French goverment is protecting artists' rights as well as those of internet users

An intense debate is raging over how to stop the erosion of creators' rights in an era swamped by free unauthorised music. It is a critical debate that I believe will shape the lives and the working conditions of creative professionals for years, even decades, to come.

France is leading the way on this issue, with its new "creation and internet" law, and where France goes, the rest of the world may follow. This is certainly not about the future of U2, the band I have managed for over 30 years. But it is about the future of a new generation of artists who aspire to be the next U2 – and about the whole environment in which that aspiration can be made possible.

I have followed this debate closely over the last two years, as a number of governments have woken up to the need to tackle the deep crisis facing their creative industries. The proposals tabled by President Sarkozy and Denis Olivennes in November 2007 gave France moral leadership in the debate, a position the country retains today. The creation and internet law is the right solution to an enormous problem. It is a fair and balanced solution, and I believe it will work in practice.

There are a few simple reasons why the new law deserves strong support. First, the crisis in our music community is real. A generation of artists, all over France, and further afield, are seeing their livelihoods destroyed, their career ambitions stolen. Investment that should help them build careers is draining out of the industry. This isn't just a shift in the business model from recorded to live music. It's a catastrophe for all the business models, old and new. It is a myth that artists can build long-term careers on live music alone. U2 will this year fill huge stadiums around the world, including two shows at Stade de France at a capacity of 93,000. That is because they have had parallel careers as recording artists and live performers since their inception 30 years ago.

The world of music is rapidly changing, and new business models are developing fast, but all of this progress is threatened in a world where 95% of music downloads see no reward going to the creator. Critics who speak of the victims as "fat record and film companies" are evoking tired caricatures, which I don't believe the majority of people today accept – certainly not those who have recently spoken to an aspiring music professional, a film producer, a TV researcher or the owner of an independent music label.

You only have to look at the sharp fall in the share of new album releases accounted by French artists in the last four years to see the damage that is being done.

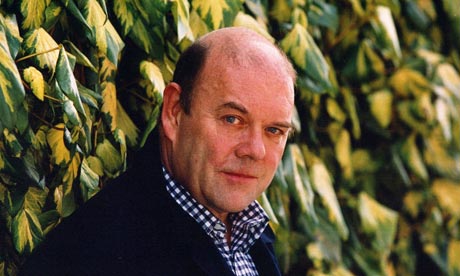

There are clearly people who oppose the new law, but I have not heard of any viable economic alternative to the system now being introduced, committing ISPs to helping protect copyright. The only other proposals offered look like solutions produced for the laboratory, not for the market place. (Photograph: PR)

In fact, the appeal of the creation and internet law is its balance and proportionality. Far from repressing freedoms as some of its critics charge, the graduated response approach goes out of its way to be fair and to respect the rights of internet users.

A system of escalating warnings, with the ultimate deterrent of temporary internet disconnection for the wilful lawbreaker, is a transparent and proportionate way of influencing consumer behaviour. And it has absolutely nothing to do with a surveillance society.

This is also a dramatic improvement on the old, unworkable solution of mass lawsuits against individuals – a policy that was pursued by record companies in the past, and to which I was always strongly opposed. That is why, by engaging with and obliging ISPs to deal concretely with infringement on their networks, the French government has made such an enlightened step forward.

The internet needs the protection of sacred freedoms, yes – but, as in real life, it also needs rules, and ones that can be practically enforced. The answer doesn't lie in thousands of lawsuits. It does, I believe, lie in a sensible strategy whereby ISPs prohibit illegal use of their networks, and actually enforce those rules.

Another simple but crucially important judgement by the government has advanced this process – namely that ISPs were not going to offer this cooperation without being required to by law.

That is not because ISP chiefs are bad people, it is because it is impossible to imagine any of them voluntarily conceding to steps that could put them at a commercial disadvantage to their competitors. Legislation to require a pan-industry solution was the right step, and a visionary one.

It is clear some still have concerns, but in many cases these are being enormously exaggerated. If we believe that artists' rights need respecting and that musicians deserve to be paid – as surveys show the vast majority of people do – then we should defend their rights in practice and not just in words. I believe a society that cares about creators' rights should not shy away from enforcing the law that protects them.

The French government should be congratulated – it is proposing a law that is a workable solution to the problem of online piracy. It has brought together ISPs and content industries in a way that will effectively protect music and film rights, while respecting important consumer freedoms. There is a crucial lesson here for governments all over the world.

This article originally appeared in Le Figaro

bron: www.ifpi.com

|